It’s time to talk about how a highly visual, well-formatted recommendations page doesn’t have much impact when it is buried on page 104. This is how we make reporting less cumbersome, particularly in a digital reporting era.

Of course your reporting will probably include a slidedeck. I mean, you could totally give a talk with no slides. People would look at you. And you would be awesome. But most of the time we have a slideshow, designed with the principles I’ve been discussing in this blog, all my books, and in every workshop for years. The idea of the presentation is generally to spark conversation and get people interested in learning more about your ideas, Rockstar.

So what next? Now that we have piqued their interest, we – what? – toss them a 300 page report and wish them luck? Sounds like a terrible way to foster engagement.

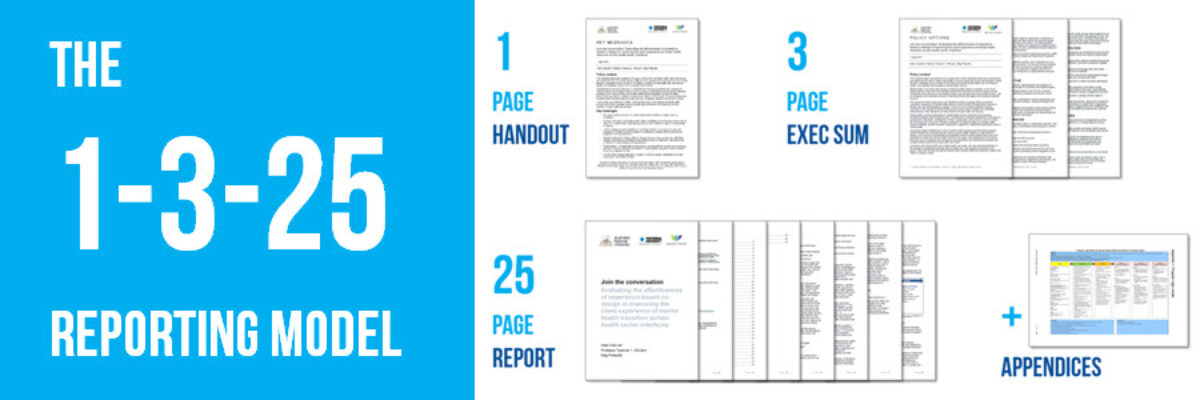

Instead of giving people a new doorstop, we can extend their engagement with a handout. Something short and sweet, like the stuff I discuss in my new book. In fact, this is where the 1-3-25 reporting model comes in handy. The 1-3-25 model suggests that our reporting include a 1 page handout, a 3 page executive summary, and a 25 page report. In each of these layers, readers gain more and more detail. They can stop anytime, having already gotten the high points from us. But it provides a scaffolding toward learning, in which each step helps the reader learn a bit more without being completely overwhelming.

This example comes from an Australian University research department that requires all researchers to publish by this model and makes templates to fit it. Smart! (See their package at http://rsph.anu.edu.au/research/projects/2015-extension-overcoming-access-and-equity-problems-relating-rural-and-remote-phc)

Of course its hard to squeeze your work into just 25 pages, especially when you include graphics and data visualizations. So you’ll need an appendix and this is where you can put things like your logic model, methodology, and p values. And it can even be a separate document that you just link to from the others.

So let’s talk about that 25 pages and what that’s going to look like.

We normally go about structuring our reports (and presentations and posters) like this:

Background

Literature Review

Methodology

Discussion

Findings

Conclusion

It feels serious and logical and rigorous. Does it look familiar? Probably so, because it’s the basic format for a journal article. It’s just that a journal article is not the same dissemination forum as the work many of us do, where our charge is focused on being useful to decision makers and we are paid to provide them actionable information.

Jane Davidson wrote a life-changing article on this matter, where she reorients us toward truly user-oriented reporting, in which we do not make the reader wait until page 104 to get to the good stuff. Today’s readers just don’t have the patience for it. They might flip through to glean highlights but few read, word for word, something so long and tedious. In fact, there’s a hashtag just for this scenario: #TLDR, which means Too Long, Didn’t Read.

The revolution in reporting is simple: Arrange the sections of the report in the reverse order. Report the findings and conclusions first. That’s what people came to learn, so give it to them. If they are satisfied, you are done! If they have questions, you have explanations, because that’s your discussion, methodology, literature review, and background. Reporting in reverse values their time. It means the C-Suite members of your audience can go on with making strategic decisions with your findings and the few statisticians in the room can hang out til the end and talk nerdy with you. Reporting in reverse puts the audience first.

This blog post is an excerpt from my new book, Presenting Data Effectively, 2nd edition. The second edition of this bestseller is in full color and includes much more on reporting for a digital reading culture. Order now.